Kiyomi Fukui

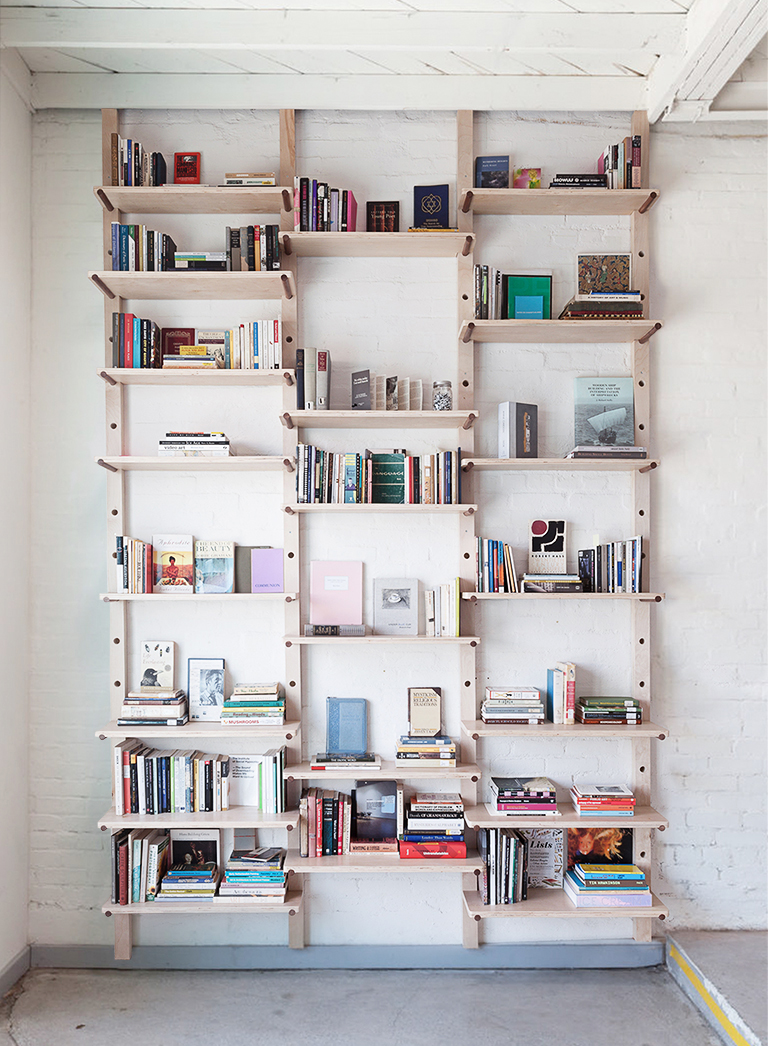

I would not characterize myself as a reader or writer; I only read what I have to, when I have to, and there’s a slim chance that I’ll enjoy the process. So when I was invited to curate the bookshelf at 3307, my instinct was one of resistance, as it meant that I would have to have actually read the books that I would be selecting. Or did it? I then realized that perhaps my aversion to reading might come from the lack of choice I’ve had throughout my life as to what I’ve read. I saw an opportunity: here was an open structure through which I could renegotiate my self-declared non-reader status, and see what it would be like to read purely for myself.

But first I had to come up with a strategy just to get my hands on books. Where are there books that I have access to? A public library.

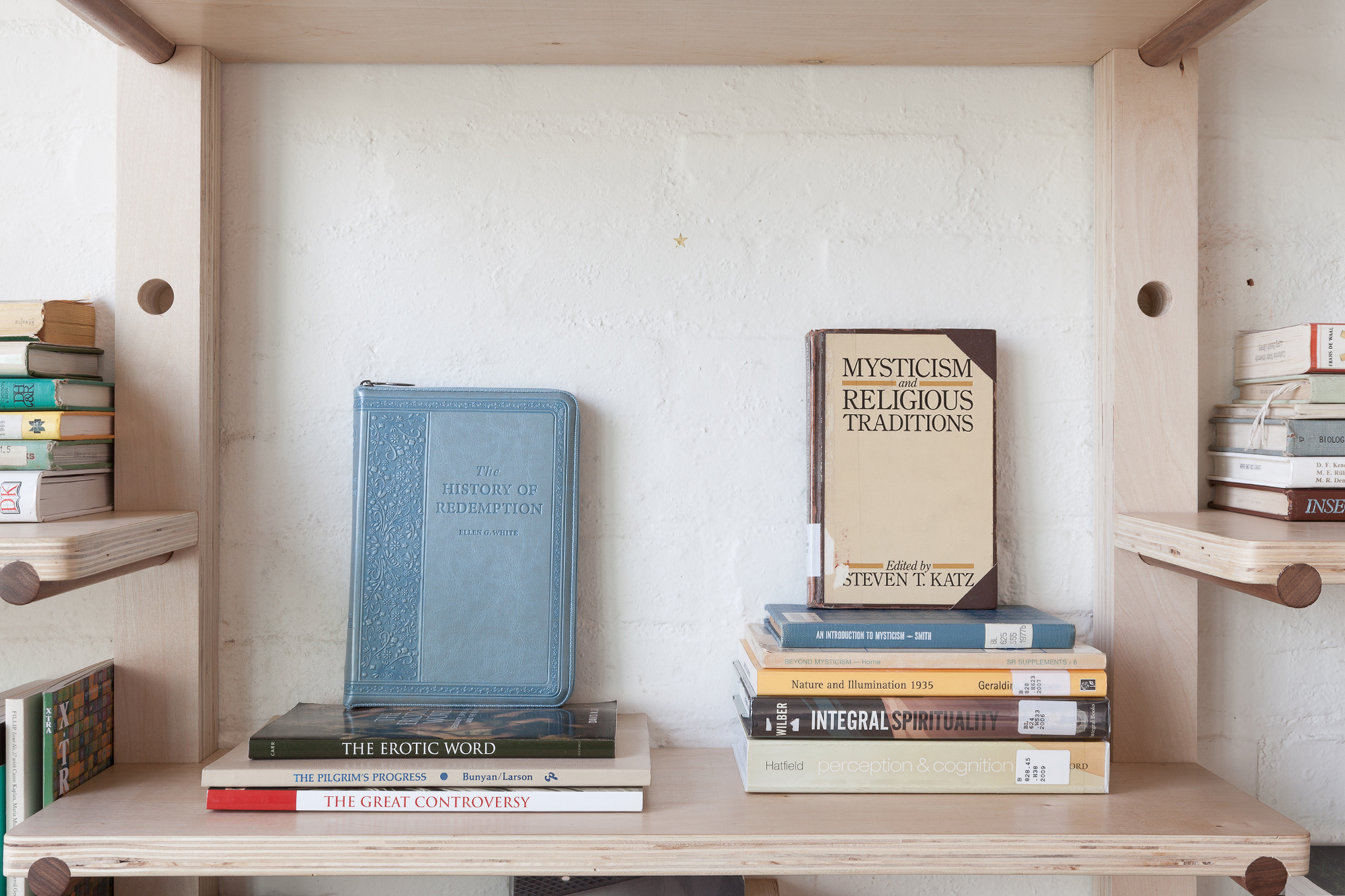

Hold on, though. Before I get into how I spent a day wandering through the stacks, let me explain how I came to select the first book, as this one belongs to the very small collection that I do own personally. You know the list of titles you’re supposed to get through, but simply can’t find the motivation to even touch? I’ve had a pile developing ever since I came to the US, when I was nineteen. These are the books that my father would send me from Japan, or drop off personally whenever he had the chance to visit. They are all related to one topic, and were given with a stringent purpose: to ensure that I understand the branch of Christianity called Seventh-Day Adventism (SDA), of which my father is a retired preacher.

I never had any intention of reading the books my father sent me. But when I met a special someone, who was not from the SDA church, my father gave us an ultimatum: to read, and finish, The Great Controversy by Ellen G. White. He had been sending this book repeatedly; we held four copies between us, but had shelved them and went on with our lives. When it came to the point of discussing marriage I realized that, despite our differences, I still yearn for my father’s blessing.

I’ll be honest. I hate the idea of having to read this book, even with my partnership at stake. But when I started to wonder about the depth of my father’s motivations, the answer was pretty obvious: fear. It’s not simply about agreeing here on earth; he is afraid that he will not get to see his daughter in heaven. Though I cannot enter the logic that produces this kind of thought, the concern itself I could understand.

And so, during my time at 3307, I’ve committed to read The Great Controversy once and for all. And I make this commitment from a place of empathy, from seeing the humanity in my father and viewing this act of reading as a small compromise in the search for a new way to connect. It is in this spirit of openness and exchange that I selected my first book.

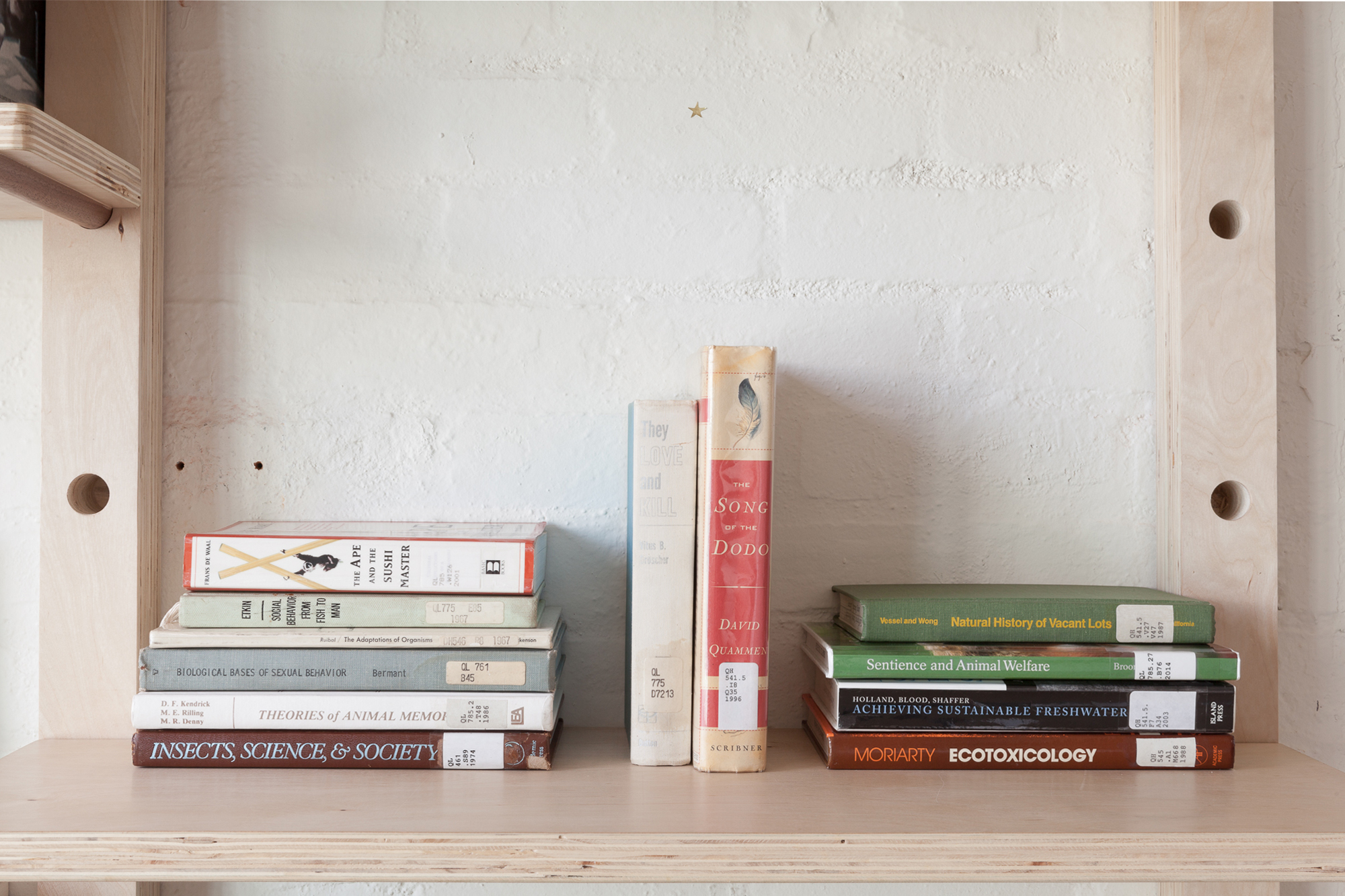

The rest of the titles came from a day spent in the library at Cal State Long Beach, where I had gone to graduate school. When I began my day of wonderment, my mind was blank, clean, empty. Perhaps in antagonism to the one book I had chosen, I began at the shelf on Buddhist philosophy and simply walked around reading titles, picking out ones that caught my eye, scanning the pages and sitting down when I was fully captivated. And each title stimulated my interest in the next. Forgive the technologically backward comparison: it felt like my experience of YouTube, or internet surfing, how my eyes clicked from spine to spine. In a way, the collection of books I ended up with is my offline search history. I had never interacted intuitively with books before, and it was thrilling.

Once I’d whittled down the selection, I saw how the titles I’d collected could be divided roughly into two categories: culture (religion, spirituality, and philosophy) and nature (environmentalism, plant identification manuals, and behavioral studies of animals and insects). But the thread running through my selection is an interest in the systems that regulate a body. An inquiry into how belief cultures regulate the experience of our bodies and the way we perceive and engage with other bodies. How do geographical conceptions of time regulate our bodies? And with respect to nature, I am fascinated by how biological processes necessitate particular behaviors, and how the structural integrity of evolution has produced such incredible variety on our planet.

I think that to understand the diversity of systems, to question them and to honor their histories and life-sustaining faculties, is the first step in fostering relations based on empathy. To not be afraid of difference. To read, if not believe.

Kiyomi Fukui is a Japanese American artist who lives and works in Long Beach. Recent exhibitions include Poetics of Relation, DAC Gallery, Los Angeles; Thread, El Camino Art Gallery, Torrance; and Bloom Polylogue, Gallery 211, Santa Ana. She received an MFA in Printmaking from Cal State Long Beach and a BFA in Graphic Design from La Sierra University. In addition to producing print-based artwork, Kiyomi also practices participatory performance and fiber arts, such as tatting and crocheting. At the core of her practice is an attempt to capture transient intimacy, irrespective of media.